IndiaSpend ResearchWire - December 4

Hello,

Since July 31, India has reported about 7.8 million new COVID-19 cases and nearly 7,000 more deaths from the disease. During this period, Bihar has re-elected its NDA government with some fascinating changes in dynamics, Donald Trump has lost his re-election bid, and three vaccine candidates for COVID-19 have shown much promise.

July 31 is also when we sent out the first edition of IndiaSpend’s ResearchWire. In these four months, we’ve added a modest 209 subscribers to our list, and formed a happy community of curious readers. With this, the 10th edition of the newsletter, we re-emphasise that we would love to hear from you. Please reply to this email to tell us what you think about the effort and what you’d like to see more, or less, of—or just send us some love!

In this edition, we discuss what lies behind the latest GDP numbers and a thought experiment on the economic value of social distancing, why India’s political push towards Atmanirbharta may be a result of serious misconceptions, how a politician’s words and actions affected the spread of COVID-19, an illustration of why you must not trust everything you read on the internet, and an explainer on why the Oxford vaccine happened so quickly (hint: you have the chimpanzees’ runny nose to thank!).

If you’ve missed the earlier editions, you can read them here.

Keep expectations low and you’ll be pleasantly surprised

India’s GDP in the July–September quarter contracted by ‘only’ 7.5%. There has been much all-round joy at this, and if that confuses you, remember that following the stupendous 23.9% contraction in the previous quarter, most of us were prepared for much worse.

Keeping expectations low—whether of the economy or of your spouse—may well be the key to happiness. But that’s a story for another day.

For now, read this excellent explainer by Udit Misra of The Indian Express, decoding the data.

He points out that the recovery is broad-based. While only one sector added positive value in Q1 (April-June), three sectors (manufacturing, agriculture and utilities) did so in Q2 (July-September). Many others witnessed a slower decline.

Contrary to expectations, the manufacturing sector added value (albeit small) even as other indicators of industrial activity performed poorly. Companies increased incomes not by selling more, but by cutting costs by sacking employees. Importantly, all “engines of growth” continue to perform far below normal, including what you and I spend on goods and services, demand for imports, and government spending.

The government is just not spending enough to boost the economy.

I recommend you read the linked piece for its solid, clear analysis. There is also a podcast. Read also this by M. Govinda Rao who reminds us that the economy was already slowing for several quarters before the pandemic struck, and while a full resumption of economic activity may take us back to the 2019-20 levels of income, accelerating growth requires addressing the economy’s structural problems.

The GDP lies

I really enjoyed this piece by economist Justin Wolfers that talks about how our perspective on the economic crisis would change if we could include the value of social distancing into our GDP calculations. He argues that if there were a pill that could treat COVID-19, we’d spend on it and that spending would increase the GDP. But social distancing does not.

So, the size of the economic crisis we see, as measured by falling GDP, is not an accurate measure of the economic crisis.

Now, while an interesting thought experiment, I am not suggesting this as a solution to economy vs health debate (nor does the article), but I do urge you to read it—to understand more about what the GDP is, what impacts it and why it is a limited measure telling an incomplete story. The article is paywalled—you can also read a Twitter thread summary here.

Errr.. No Minister

India’s external affairs minister S. Jaishankar recently came down heavily on globalisation, trade agreements and open markets, blaming these for India’s challenges with deindustrialisation, low employment and an “over-dependence on imports”.

To see why this is flawed, read this very instructive paper by India’s former Chief Economic Advisor Arvind Subramaniam and Shoumitro Chatterjee. They present evidence to show that India’s increasingly inward turn is based on three serious misconceptions:

That India’s domestic market size is big: Subramaniam and Chatterjee show that India’s population size obscures market realities and its “true” market is only a fraction of its own GDP (15-45%), about 15-20% of China’s true market size, and only 1.5-5% of the global market.

That India’s growth has been based on domestic—not export—markets: They remind us that India has been “an exemplar of export-led growth” in the three decades since the early ‘90s.

“Its export growth has been positively East Asian Tigeresque, which in turn has driven and/or sustained high GDP growth.”

That export prospects are dim because the world is deglobalising: They point out that deglobalisation is not inevitable, and structural changes could boost demand for tradable services; and that India is small enough to gain market share even when global trade grows slowly. Remember also India’s vast potential to increase unskilled labour exports, which India is “vastly under-exploiting”.

This is a very good, easy to read paper with lots of data to chew on. For an even simpler piece on the argument, read this by journalist Puja Mehra. Mehra argues, and I am inclined to agree, that the Minister’s take is less ‘poorly-researched’ and more an attempt to lend credibility to the obviously political anti-trade narrative du jour. Read also his more recent interview here where his response to the trade question is far more measured.

But should you care about what politicians say at all?

As the COVID-19 pandemic unfolded, the Brazilian president Jair Bolsonaro—the“Trump of the Tropics”—encouraged people to go out, made appearances in stores, markets and rallies on the streets, and dismissed the virus as “just a little dose of flu”. Here’s a very cool paper to show us what that did.

Combining electoral and geo-localised mobile phone data from 60 million anonymous devices in Brazil, Nicolas Ajzenman, Tiago Cavalcanti and Daniel Da Mata show that after Bolsonaro publicly and emphatically dismissed the risks associated with the COVID-19 pandemic, social distancing measures taken by citizens in pro-government localities weakened compared to places where political support of the president is less strong.

“…this impact is driven by localities with relatively higher levels of media penetration, municipalities with presence of active Twitter accounts…”

Now, some of this is thanks to the power of asymmetries in information between governments and citizens, which are significant even in the best of times and can be monumental in a crisis such as this one. But also, unsurprisingly, political leaders’ actions and speeches are important tools that shape people’s beliefs and affect behaviour. Read here a good summary of this paper with links to other related research.

There is enough evidence to show that you can’t just ignore daft statements from those in power.

A story in 3 charts

In a great example of how you need to be a critical consumer of content on the internet, Columbia University’s Adam Tooze not so long ago called out the Financial Times for the following chart on global CO2 emissions in this piece.

Unless you’re familiar with these trends, this chart will tell you that while total global emissions since 1900 have surged, per head emissions have stagnated. This means, it is rising populations that have driven CO2 emissions up, even as each person is adding only as much as they always did. (If I may loosely translate, this means that poor countries with their many people are responsible for rising CO2 emissions.)

This is factually incorrect. Per capita CO2 emissions have in fact more than quadrupled over this period.

It is economic activity that has driven the surge in global CO2 emissions. Not just more people on the planet.

The pink line (tonnes) in the chart above is climbing up, but because it is plotted on the same axis as the blue line (billion tonnes), you can’t see that. This is why you add a secondary axis. Or make a separate chart.

Hannah Ritchie pointed out that CO2 emissions have grown at a much faster rate than population.

The FT responded and changed the chart in the article to the ones below, which make a lot more sense.

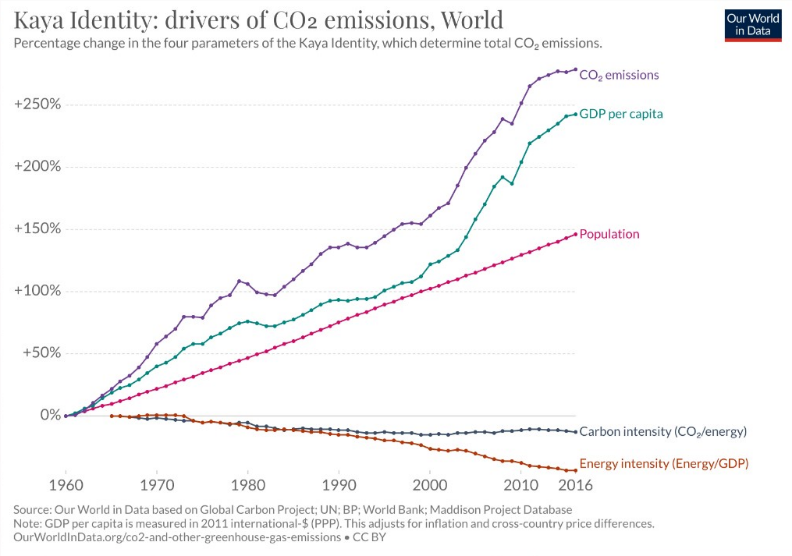

As an aside, Hannah’s chart also made me look up the Kaya Identity, a neat equation that expresses total emission levels of carbon dioxide as the product of four factors: human population, GDP per capita, energy intensity, and carbon intensity. The Identity is a specific form of the more general I = PAT formula which says that human impact on climate is a function of three factors: Population, Affluence and Technology.

Don’t miss this

Finally, if you’d like to read some superlative science writing, I recommend this by James Gallagher of the BBC: the real story behind how the Oxford vaccine happened so quickly.

If you think the work on the vaccine started when the pandemic began, you’d be wrong. Scientists had been prepping to tackle a “Disease X” ever since the Ebola outbreak claimed thousands of lives in 2014-16, and someone realised that the world should’ve done better.

Sincerely,

Amee Misra

Contributing Editor, IndiaSpend

Twitter LinkedIn

You are receiving this email as you are subscribed to the IndiaSpend mailing list. Any views or opinions are the author's own.