IndiaSpend ResearchWire - March 5

Hello,

In today’s edition, we discuss the cross-subsidisation of India’s domestic power and how that’s hurting industry, the relationship between money and happiness, the impact of the COVID crisis on India’s women workers, why you shouldn’t believe every map or index that comes your way, and a delightful book recommendation.

If you have missed any of our earlier editions, you can read them here.

You can give a subsidy, but can you take it away?

Ama Baafra Abeberese finds that subsidies on household electricity in India come at the expense of India’s firms, reducing both their growth and output. These are driven partly by political incentives (voters like politicians who give cheap electricity) and partly by the need to provide affordable electricity to the poor.

This cross-subsidisation has meant that India’s industrial sector has historically faced higher prices that its households or agriculture.

This is in direct contrast to developed countries where industrial users typically pay lower prices thanks to their high consumption and hence economies of scale.

Reducing this cross-subsidisation in electricity pricing in India has been on the agenda for some time now. But surely, we need to provide cheap power to the poor.

Yes, and that’s what direct benefit transfers (DBTs) should be able to do—instead of a blanket subsidy for you, me and everyone else, DBTs can enable targeted support to those who really need it. But it isn’t quite as straightforward. Read Sudipto Mundle in this good, albeit old piece on the pros and cons of using direct benefit transfers to deliver subsidies.

A move from blanket subsidies to Direct Benefit Transfers requires strong state capacity and an iron political will.

Taking away or lowering subsidies is tricky business and often a political minefield. India’s Ministry of Finance has already announced an indefinite pause on its ambitions to lower food and fertiliser subsidies even as the Economic Survey had called India’s food subsidy bill “unmanageably large”.

Can money buy you happiness? Sort of.

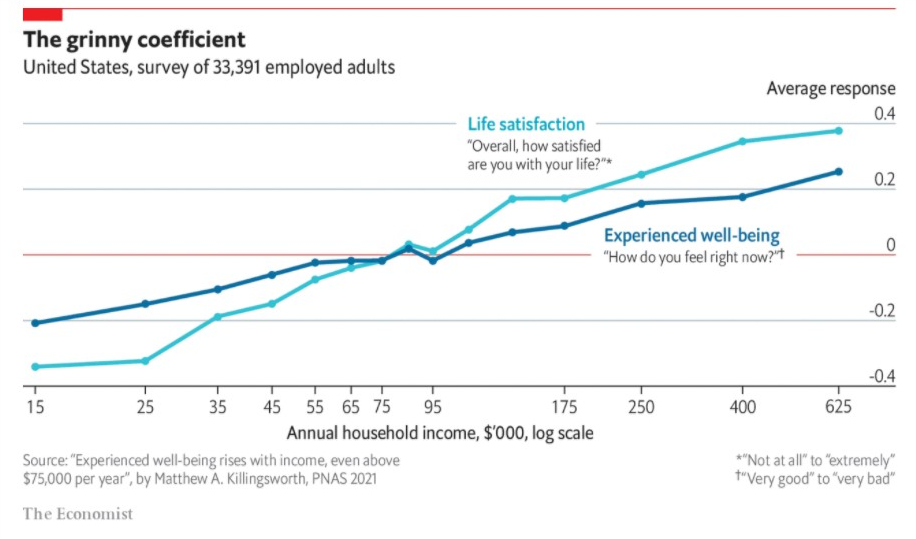

Previous research by Nobel laureates Angus Deaton and Daniel Kahneman showed that you felt better about your life as your income increased, but only up to a point. After an annual income of about $75,000, they argued, it didn’t matter. That gave me solace.

But it turns out that there’s more. New work by Wharton’s Matthew Killingsworth finds that there is no dollar-value plateau at which money becomes less important.

Happiness continues to increase with income – the more money you have, the happier you get.

But there are two important caveats: First, the more happiness you want, the more expensive it gets. Simply put, an extra dollar will bring you less joy if you’re rich than if you’re poor. Elon Musk did shrug at the news of gaining billions in his net worth.

Second—thankfully—there continues to be more to life than money. Only a small percentage of the overall variation in happiness is explained by differences in income.

A good piece here in The Economist on this research, and the full paper here. A non-paywalled blog here if accessing the The Economist is tricky.

Where are the women?

If you care about women’s employment, I recommend this piece in The Economist on the calamity that COVID-19 has been for women’s employment in India. Quoting data from CMIE’s surveys, the piece argues that men who lost their jobs during the lockdown were eight times more likely to find another within a few months than women who had lost theirs.

The share of women in India’s labour force had been falling even before the pandemic; the crisis exacerbated the inequalities.

Women in India have traditionally held lower-paying and precarious jobs that were easy to lose. The disproportionate care burden on women also meant that far more women pulled out of the workforce to look after children who stayed home from school.

Watch also Ashwini Deshpande here on what it will take to bring women back in the labour force, and on jobs more generally, a very good piece here on why the budget won’t bring the jobs we need it to.

Not every index makes sense

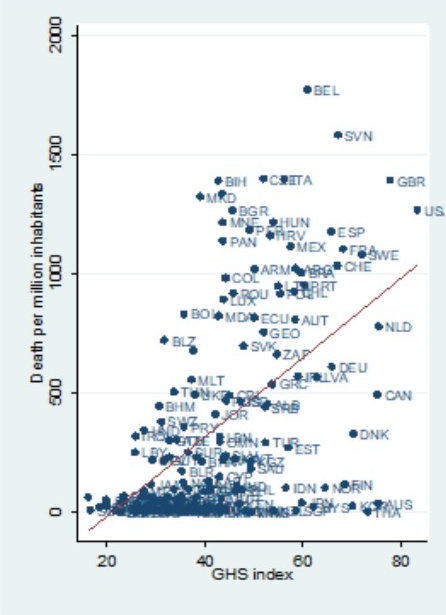

In 2019, the Johns Hopkins University’s Bloomberg School of Public Policy, Nuclear Threat Initiative, and the Economist Intelligence Unit put together the Global Health Security Index (GHS)—ranking countries on their readiness to face a large disease outbreak.

The index looked at 195 countries, using 34 indicators, 85 sub-indicators and 140 questions, combining them across six categories—to produce a composite score of a country’s health systems, immunity, healthcare workforce, the ability to carry out real-time surveillance and reporting, and more.

The United States was named the country that was best prepared for a pandemic—with the strongest measures in place and a score of 83.5 out of 100. The UK came second with 77.9, followed by the Netherlands with 75.6.

But that’s not the way this cookie crumbled, is it?

Read this by Branko Milanovicblog on the trouble with such “mashup indices”. Comparing the rankings on the index with data on COVID-19 deaths across countries, he shows that the index is “not only unable to predict outcomes … but its rankings were often the inverse of the currently observed success rankings”. Countries like the US, the UK and the Netherlands that did well on the index had some of the worst death tolls from COVID-19.

“The GHS index is positively related to the rate of deaths—the very opposite of what we expect.”

Branko reminds us to be wary of similar indices that are often put together for other things—like corruption or transparency in government. I’ll just remind you to not trust everything you see on the internet—just because there’s a map doesn’t mean it makes sense.

The seven-year-old recommends

I have an unusual book recommendation this fortnight: It comes from the library of my seven-year-old. The folks at Usborne do some excellent non-fiction books for kids and I’d recommend them all—but for the purpose of this newsletter, allow me to introduce you to Usborne Economics for Beginners.

With cartoons, real world examples, simple language and great clarity, this book introduces you to the most basic concepts in economics—in a fun, intuitive way.

While it’s a children’s book, it isn’t only for children.

If you’ve ever had questions about who fixes prices in the economy, why you should pay taxes, why are Instagram influencers so successful, why can’t poor people just work harder, or why can’t we keep printing more money, this is the book for you.

My son read about the economics Nobel and asked if I’m likely to get it. I responded with a quiet smile, because why jinx it?

If you’ve enjoyed reading our newsletters, please take a moment to tell people about it. As always, we would love to hear from you about what we can do better. You could reply to this email to tell us, or use this short feedback form.