IndiaSpend ResearchWire - October 23

Hello,

In this edition of ResearchWire by IndiaSpend, we discuss why it is better to be a woman in South India than in the North, a tool that can show you what poverty looks like and what it means for protection from COVID-19, the nuts and bolts of a well-functioning digital payments system, a proposal for an urban jobs guarantee programme, explainers on externalities, and an excellent illustration of a first world problem.

If you’ve missed the earlier editions, you can read them here.

If you must be a woman in India, stick to the South

Alice Evans sure knows how to keep things interesting. After her blog on why Indian men live with their parents, she has moved on to another equally unemotional, congenial matter that is unlikely to ruffle any feathers: Why do the north and south of India treat their women differently?

What explains the fact that, relative to women in North India, women in South and North East India are more likely to survive infancy, get educated, choose their own husbands, move more freely, or work alongside men?

Alice looks at the literature on a range of issues to find the answer: Is it colonial history? Practices of cultivation and differences in soil? Incidence of poverty? Mughal conquests and purdah?

I won’t give you the answer—read the blog. Alice writes well and puts in more work in a blog post than many people do in their dissertations. It reads like a nice, nerdy whodunnit and has maps that are sure to rile you up!

What does poverty look like?

Caitlin S. Brown, Martin Ravallion and Dominique van de Walle put together an index earlier this year to assess whether poor households have what it takes to protect themselves in this pandemic. Using data for one million sampled households across developing countries, they found that over 90% of the world’s poor in developing countries do not have the capacity to protect themselves from COVID-19.

The living environments of the majority of the world’s poorest do not allow them to follow WHO recommendations of washing, isolating, and treatment.

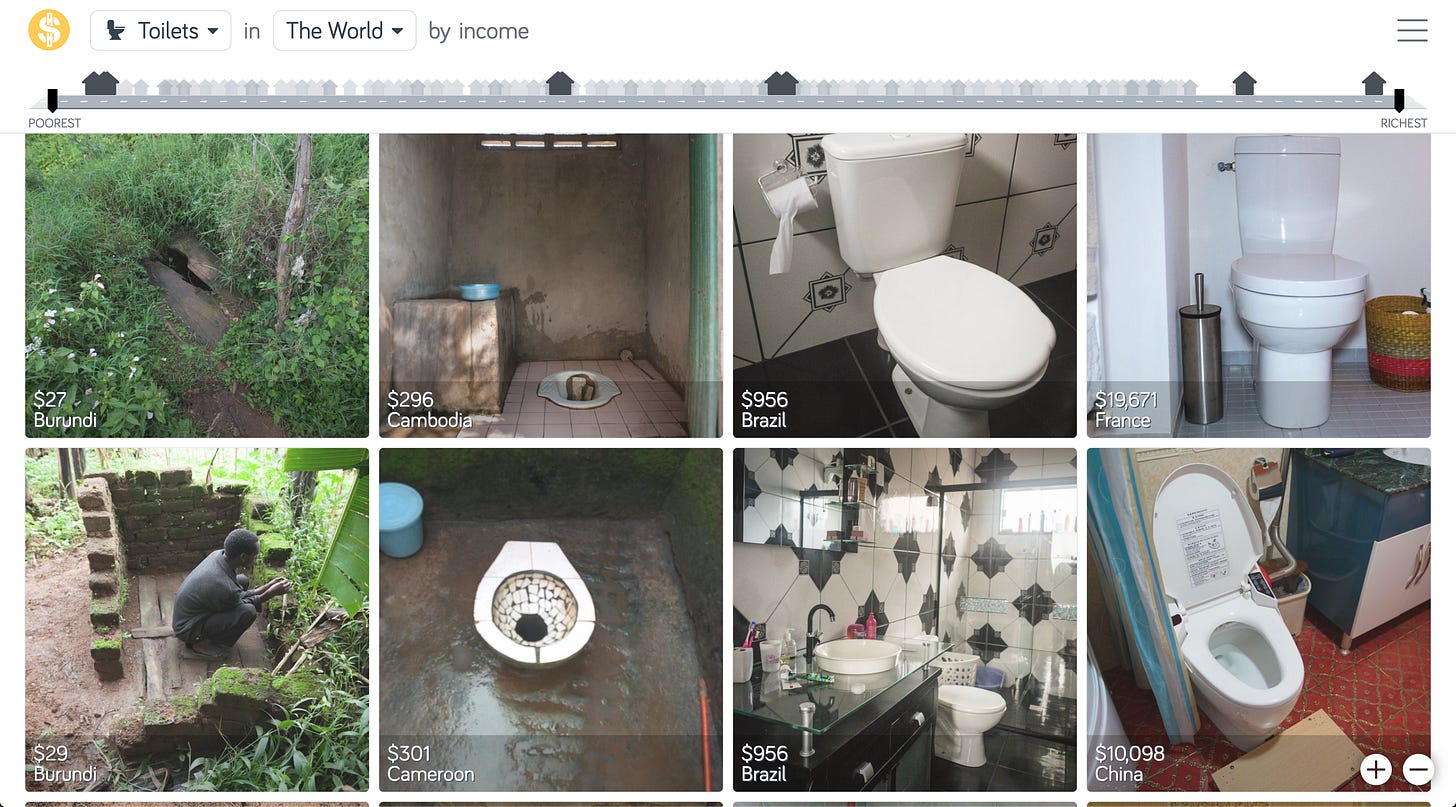

The numbers are all in the piece but let me introduce you to a nifty tool that can show you what being poor looks like. The brain child of the Swedish designer Anna Rosling Rönnlund, Dollar Street is a tool to visualise different levels of deprivation.

The screengrab above shows what toilets look like at different levels of income. You can also check for soap, alcoholic drinks, drinking water, toys, families, and more. Or toggle for different levels of income, regions and countries. I like to use it to put a face to the data. It’s also a great tool for presentations (the whole website is), or to show to your children when they’re being ungrateful.

The devil is in the details

Over the last few months, governments around the world have had to deliver benefits and relief on a scale never seen before; and using digital technology has been at the heart of this process, albeit with varying degrees of success. Read this by Alan Gelb and Anit Mukherjee of the Center for Global Development on the lessons emerging from these exercises.

Countries that had made investments in a strong digital infrastructure—including ID and payment systems and social registers—have generally been able to implement and disburse emergency assistance programmes more rapidly than those without these assets.

At the same time however, the strain of the pandemic has revealed several areas for reform: The capacity of such systems to handle large and sudden transfers, the propensity of people to cash out benefits immediately leading to crowds at pay points, concerns of data privacy, ways to identify the ‘new poor’ or those left out of traditional social security databases, and more.

Also read this by Anit for a very good nuts-and-bolts story of Bihar government’s Corona Sahayata (Assistance) Scheme launched to support Bihar’s migrants. Even as the scheme managed to reach over 2 million people within few weeks of its launch, exclusion remained a daunting challenge.

I suggest two takeaways from these pieces:

First, investments in digital infrastructure can address many of the “how to pay” constraints; if you’re on the grid, you’d get your money and you’d get it fast. But the key challenge for social benefits transfer in India remains around “who to pay”. India continues to use 2011 data to count its poor in 2020, and severely undercounts its migrants thanks to an inaccurate data classification.

Second—and in some way linked to this—digital first programmes don’t always work for the poorest. They are the ones without smart phones and without the means to go about getting their details included or corrected in government databases. As Anit notes, Bihar’s programme was no exception.

“People with smartphones could use the Android application (iOS was not supported) to register for the program while those without it had to overcome additional hurdles to complete the process. ..many people faced problems entering correct bank account details, dormant accounts requiring KYC, and to cash out once the assistance was received.”

Do you know what externalities are?

You should. They are arguably the most real-world relevant concept in economics and critical to understanding much of public policy. Externalities cause markets to ‘fail’ or be ‘imperfect’, and as economists Sarah Cohodes and Susan Dynarski argue in the NYTimes here:

“.. 95 percent of economics is about the imperfections of markets, and how the government can correct them.”

Using the decision to open colleges in the US at this time as an example, the economists show what happens when individual actors, choices and incentives are left to their own devices in a market rife with externalities.

For another example of why externalities matter, watch this excellent explainer of the economics behind the COVID vaccine by Alex Tabarrok, economics professor and blogger extraordinaire. In a short (less than 6 minutes) video, he shows you why you need to worry less about vaccines manufacturers making too much money from a COVID-19 vaccine, and instead worry about how to ensure that they make enough.

DUET? Do it

As survey after survey comes in with reports of rising economic distress, skipped meals and lost incomes among the urban poor, the Indian government is considering an expansion of its rural employment guarantee scheme (MGNREGA) to urban areas. Economist Jean Drèze—one of the architects of MGNREGA—has a proposal.

Through a scheme called Decentralised Urban Employment and Training or DUET, Drèze proposes the creation of a lasting institution “as an antidote to urban unemployment and urban decay”. The government would issue ‘job stamps’ and distribute them to public institutions such as schools, colleges, shelters, jails, municipalities etc. These institutions would convert each job stamp into one person-day of work and offer work to registered workers. To avoid collusion, these would be assigned by an independent placement agency. The wages would be paid by the government directly into the workers’ account on the presentation of job stamps.

While ensuring jobs is key, there is something that is often missed in such a rights-based approach to welfare. Unless DUET addresses the critical issues of limited state capacity (you can’t implement new and innovative ideas using the same old rusty framework), and excessive centralisation (genuine devolution of both powers and finances is critical), it is unlikely to go very far.

A wide range of experts have expressed their views on the proposed scheme and you can find them at the bottom of this page.

It could be worse

Finally, if you think you’re having a bad week, I recommend you stop moaning and read this FT piece on how others have it worse. Written by someone “blessed with an inheritance as well as a venture-capitalist husband”, the piece outlines the writer’s many challenges of living in South Kensington when even Harrods has shut down. Her struggle to find the right work wardrobe is resolved only when she can move from her Chanel tweed blazers to Olivia von Halle silk pyjamas “in colours guaranteed to make the dullest Zoom meeting come alive”. She is grateful for the police officers in Hyde Park who turn on the lights of their patrol car to “amuse her children”, and her Chelsea gym that delivers protein shakes and artisanal coffees to her doorstep so she can escape the horrors of “coronacarbs”. Read it—it is not a spoof.

Sincerely,

Amee Misra

Contributing Editor, IndiaSpend

Twitter LinkedIn

You are receiving this email as you are subscribed to the IndiaSpend mailing list. Any views or opinions are the author's own. A previous version of this newsletter incorrectly attributed Dollar Street to the Swedish economist Hans Rosling. This has now been corrected.