IndiaSpend ResearchWire - Sept 11

Hello,

In the fourth edition of ResearchWire by IndiaSpend, we discuss why Indian men live with their parents, the economic benefits of cutting emissions, what the latest GDP numbers mean, why the mother-in-law matters to policy, and a survey on how parents choose schools for their children.

If you’ve missed the earlier editions, you can read them here.

Why do Indian men live with their parents?

Dr Alice Evans has a very good, data-led piece on why most Indian men live with their parents. It created a bit of a mini Twitterstorm, getting everyone’s hackles up about India’s culture and family values.

To be clear, she is not making a moral argument. She is analysing why it is that India’s rapid economic growth (remember that?) since the 1980s did not lead to a disappearance of extended families—like it did in East Asia, for example.

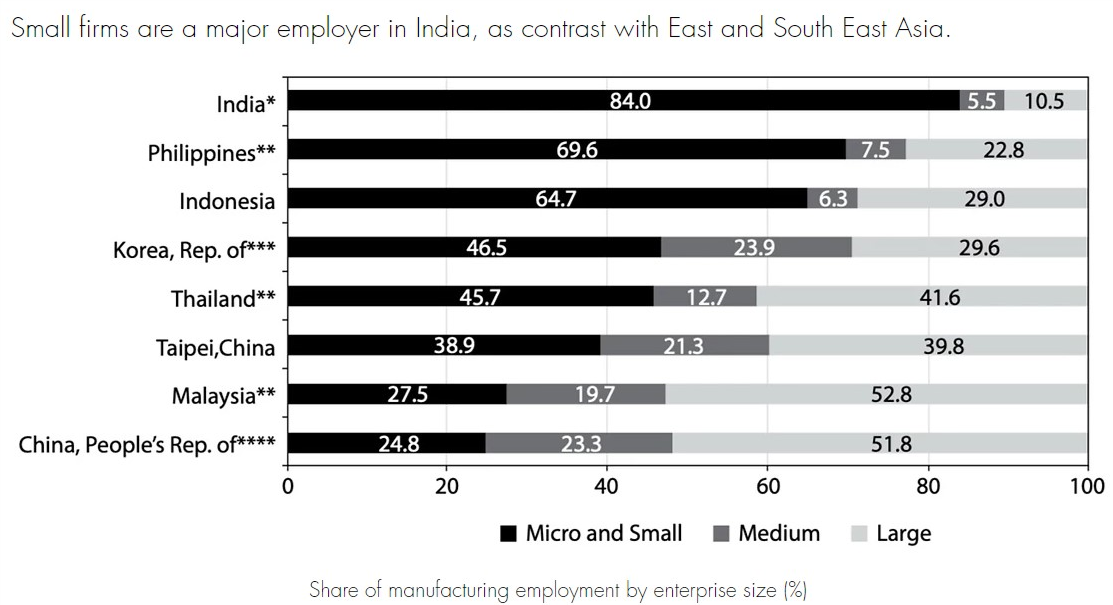

Dr Evans finds that the answer lies in the kind of economic development India has experienced. Most Indians tend to work for small family-owned businesses, which strengthens multigenerational households.

You live together because you work together in a business that you own together.

I recommend you read the post. It is a masterclass in how to weave diverse pieces of evidence into one narrative and make a case. It will also give you lots of interesting facts to pepper your dinner party conversations with. For instance, did you know that joint families in the north of India are four times more common than the south? Or that female employment in South Asia is associated with deprivation so women gain status by withdrawing from the labour market?

I’ll admit the title of her post did irk me a little bit: Why frame it as an aberration and the alternative as the norm? The actual piece does not do that. But I was mollified when she promised that she will look into another equally important question: “Why is the West weird?” And she did, here.

Even the economics makes sense

A good piece here on the economic rationale for a well-funded government response to climate change. It argues that global climate action need not come at the expense of sustained economic growth, and that not taking any action will “most certainly” block growth.

The benefits of implementing the Paris Agreement on climate change far outweigh its costs: The health benefits alone could exceed investment costs 1.5-2.5 times.

Read also The Economist on how COVID-19 has created opportunities to flatten the climate curve. And if horror is a genre you enjoy, read this by the FT.

If academic arguments and data don’t speak to you, read these real-life stories on the impact of climate change on communities, businesses, and people in India. This is excellent reportage on a range of climate-change impacts including Yamuna’s dead fish, how cotton cultivation in Odisha is sowing the seeds of a climate crisis, and the impact of the rain going rogue in Thane. Read also this excellent IndiaSpend series on India’s climate change hotspots.

Also know that SUVs were the second largest contributor to the increase in global carbon emissions from 2010 to 2018.

The GDP Nosedives

You may have heard that India’s GDP has contracted by 23.9% in the first quarter. Read this for a good Econ 101 explainer. The decline is not for the year or since the preceding quarter—but when compared to the same quarter in the last year.

“In other words, the total value of goods and services produced in India in April, May and June this year is 24% less than the total value of goods and services produced in India in the same three months last year.”

Except agriculture, all major sectors have taken a nosedive. Some estimates say that this will translate into a 7% annual decline. SBI’s Chief Economist thinks we’re looking at 10.9% decline. Goldman Sachs estimates 14.8%. If you’ve wondered why everyone has a different forecast, remember that forecasting is very tricky business, and that making economic predictions now is useless.

If you don’t like looking at GDP numbers, I came across a more ‘fun’ way (amazing what passes off as fun when you do the job I do) to understand the economic impact of COVID-19: World Bank economists show that electricity consumption and the intensity of nighttime lights observed from space make for good proxies to monitor India’s economic activity. They also use these to assess the impact of the pandemic on India’s economy. Using these to assess the impact of the pandemic on India’s economy, and based on their observed relationships to economic activity in the past (1 unit of additional economic activity is associated with 1.3 units additional electricity consumption), they find that the economic impact of the pandemic has already been between $160 billion and $175 billion, or between 5.6% and 6% of India’s GDP.

You can read a summary blog here, and a detailed working paper here.

The Mother in Law

Based on a survey in Jaunpur (Uttar Pradesh), a study by Dr S. Anukriti and others shows that a young, married woman who lives with her mother in law has 36% fewer close peers outside the home—when compared to one who does not. Why does it matter? As far as I am concerned, it should matter solely because adult women should be able to make their own choices.

But if you must have a more development-y reason, the research finds this inability to make friends reduces young women’s access to, and utilisation of reproductive health services.

Having an additional close outside peer increases a woman’s likelihood of visiting a family planning clinic by 67 percentage points, and her likelihood of using modern contraceptive methods by 11 percentage points.

So what’s the policy implication?: When MILs act as “gatekeepers”, government initiatives that rely on tapping women’s social networks to spread messages and information around family planning are meaningless.

The research also points to a “potential misalignment of fertility preferences, and asymmetry of information and bargaining power between the MIL and DIL”—which loosely translates into one-wants-many-grandchildren-while-the-other-wants-to-just-get-on-with-her-life. It is proposed that family planning programmes take note of this intra-household dynamic, like they do in the case of spousal conflict over contraception.

Der Aaye, Durust Aaye

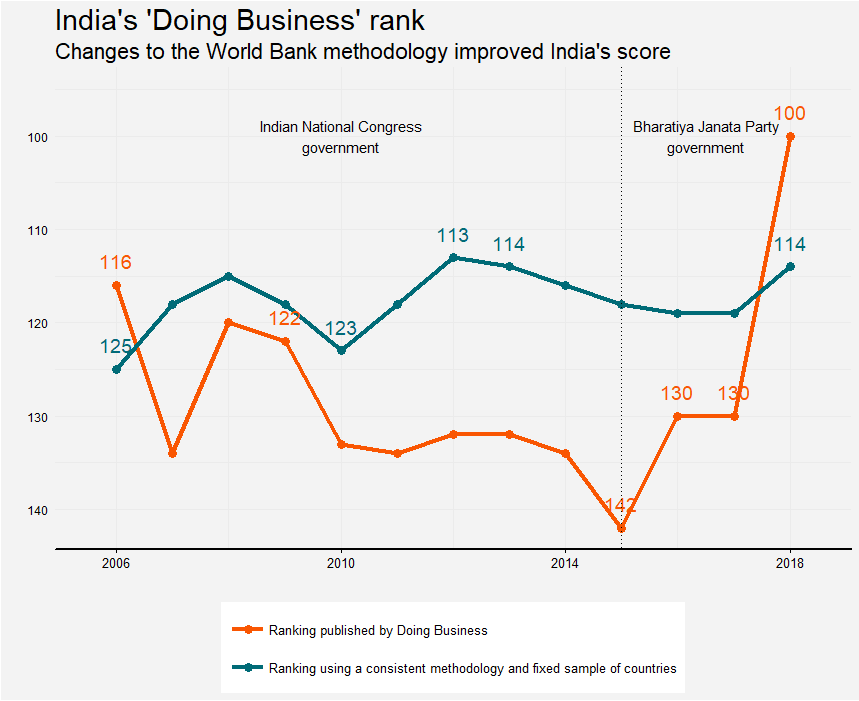

The World Bank have paused the publication of their Doing Business Report and initiated an audit of its data and methodology. Given the many concerns over the report’s rigour, usefulness, and allegations of influence by country governments—this was a long time coming. Two Chief Economists of the Bank recently resigned in quick succession, including Paul Romer who quit soon after calling out Chile’s rankings for methodological issues and political influences.

Read this excellent 2018 piece by Justin Sandefur of the Center for Global Development on how it was the changes in World Bank methodology, and not reform that made India “jump” the ranks. For instance, when you add new countries to an index, the rank of existing ones will change.

Nepal’s experience shows that on-ground reform is not necessary to move up the DB ranks. The DB rankings have also been called out for a more conceptual issue—they do not consider the fact that regulations have benefits, not just costs.

If you enjoy gossip, see this for a spat between World Bank colleagues and researchers questioning their methodology. The founder of the Doing Business Index called critics “Marxists” on a public platform and you can watch it here.

For more on doing business: Contract enforcements and a functioning judicial system are at the heart of business reforms. Read this for stories that underline the urgency of how Indian courts need to up their game—including one on how it took them 38 years to resolve a turmeric forgery scandal. There are nearly 40 million cases pending across the country’s courts, many for over 20-30 years. This is the sort of thing that makes investors nervous: Land acquisitions take forever, labour disputes go nowhere, non-disclosure agreements mean squat, and signing a contract is at best an act of good faith.

A market isn’t going to solve this one

See this for the many complex factors that drive how parents choose schools for their children in India. A survey of 1,210 families and 121 schools across four Indian states (Chhattisgarh, Karnataka, Rajasthan and Uttarakhand) found that perceptions of teaching-learning, discipline and safety are important determinants of school choice in India.

But is it really a choice if you’re basing it on false information and half-truths?

The survey found that not everyone who thinks they’re going to an English medium school is really going to one.

Only 25% of parent’s perception of English as the medium of instruction in their children’s schools matched with reality.

More than half of the children who were supposed to be attending English-medium schools were studying in a dominant regional language. Around 18% were going to a school that had books in English, but with teachers translating those into the dominant regional language while teaching. There was also a mismatch between parents’ perception of teacher quality and the reality.

These are textbook information asymmetries: indiscriminate market-based schooling solutions do not work when individuals are unable to make informed choices.

Vouchers are not a substitute for a functioning public-school system.

See also a comprehensive piece here in the context of India’s New Education Policy (NEP) on why learning in the mother tongue is effective, but difficult to implement.

Sincerely,

Amee Misra

Contributing Editor, IndiaSpend

Twitter LinkedIn

You are receiving this email as you are subscribed to the IndiaSpend mailing list. Any views or opinions are the author's own.