Hello,

In this edition of ResearchWire by IndiaSpend, we discuss why large firms matter to developing countries, how patriarchy isn’t so easily smashed, why politicians don’t care about migrants, and what lies behind India’s plummeting GDP. Also, a rap song you mustn’t miss and Shakira’s tax woes.

If you’ve missed the earlier editions, you can read them here.

Large firms matter

While there is enough written—and read—about the role of small and medium firms in development, a new World Bank publication points to what is often overlooked: the role of large firms in developing countries.

Large firms support a range of development objectives in ways that smaller firms do not.

They are more likely to innovate, export, and adopt international standards of quality. Much of this comes from advantages of scale and increased productivity—a challenge for developing country firms that often remain small.

Limited market size can be a barrier and explains why the growth of mobile phones in Kerala—that allowed fisherfolk to look for buyers outside their local market—increased the size of the efficient ‘firms’ and pushed the low-quality firms out. But unequal market power between buyers and sellers means that firms do not always prioritise productivity either—it can take a back seat to managing complex relationships with buyers, who can easily take their business to the factory down the road.

The linked publication argues that large firms are often born large, or with some or many features of ‘largeness’. So, what's the policy implication?

For developing countries, it means that they need to create conditions that enable the birth of large firms:

Opening markets to competition, breaking oligopolies, removing unnecessary restrictions to international trade and investment, and establishing the rules and the state capability to prevent abuse of market power; and

Ensuring that people have the skills, technology, intelligence, infrastructure, and finance they need to create large ventures.

To be fair, these sound more or less like what countries need to do to enable their small firms to grow to be big one day. I suspect the difference would be in the scale and type of support, say across the levels of finance you need to provide or the type of technology you need to enable access to.

For background on the issues around firm capabilities and economic growth, read this evidence note from the International Growth Centre.

Don’t underestimate the patriarchy

When India's Supreme Court declared equal property inheritance rights for men and women in 2005, we celebrated it as a step towards gender equality and all that’s good for women. But it looks like patriarchy may have won yet again.

In this paper, Sanchari Roy, Sonia Bhalotra, and Rachel Brulé look at the most defining feature of gender inequality in India—the preference for sons over daughters—and find that giving women rights to the family property exacerbated this preference. Children born after the reform in families with a firstborn daughter are 3.8 to 4.3 percentage points less likely to be girls.

The inheritance reform raised the costs of having daughters and encouraged female foeticide using sex-selective abortions.

The reform was also followed by a rise in female infant mortality (relative to male) and an increase in the tendency for families without a son (or their desired number of sons) to continue having children. The law raised the stakes and made people even more determined to have a boy. You can read a summary article on the paper, or tune into a podcast (25 minutes) to know more.

What lies behind the plummeting GDP

If numbers don’t make you nervous, I recommend this data-led piece for its excellent assessment of India’s current macroeconomic woes. Partha Mukhopadhyay of the Centre for Policy Research uses a range of data sources to examine the extent and nature of India’s GDP fall, and the sources of any green shoots.

He shows that India’s per capita income has fallen to a level now that is the same as when Prime Minister Modi first took office in 2014.

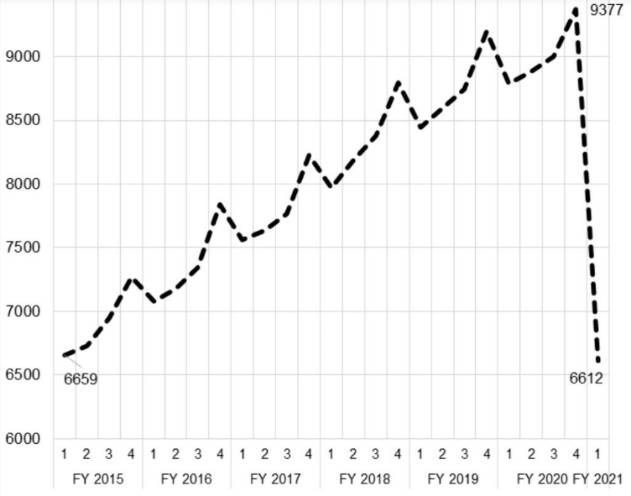

Monthly per capita GDP (constant 2011-12 prices) (1Q FY 2015 to 1Q FY 2021)

The fall in consumption (26.7%) is larger than the fall in GDP, even more so when you adjust for the fact that spending on essentials will reflect their increased prices in the period. Investment has been almost cut in half, falling by a stupendous 47%.

"Capital formation as a share of GDP has fallen to levels last seen when three-fourths of the Indian population had not yet been born."

Partha argues that the economy’s demand drivers have dried up—both domestic or external—and recommends that the Modi government approach economic policy “with the same boldness with which it instituted the national lockdown”. Read the piece for a comprehensive picture of India’s economy at this time, and all the data you’ll need to quote any time soon.

Whenever, Wherever, Just Pay Your Tax

How different would the world be if the rich just paid their taxes? Read this fascinating account of how “with the devotion of a diehard fan and a detective’s eye for detail”, Spanish tax authorities used social media to corner Shakira for tax evasion to the tune of €14.5 million. That’s right. Shakira, of the honoured-by-the World-Economic-Forum-for-her-commitment-to-philanthropy fame, fears death and taxes just as much as you and me. Or at least her advisors do.

Tax evasion by the rich is a problem and them giving money to charity doesn’t even begin to solve it. A lot of philanthropy is the elite spending on elite causes—and benefits the super-rich. Charity funds also don’t always go to a country’s own priorities but reflect the donor’s passion.

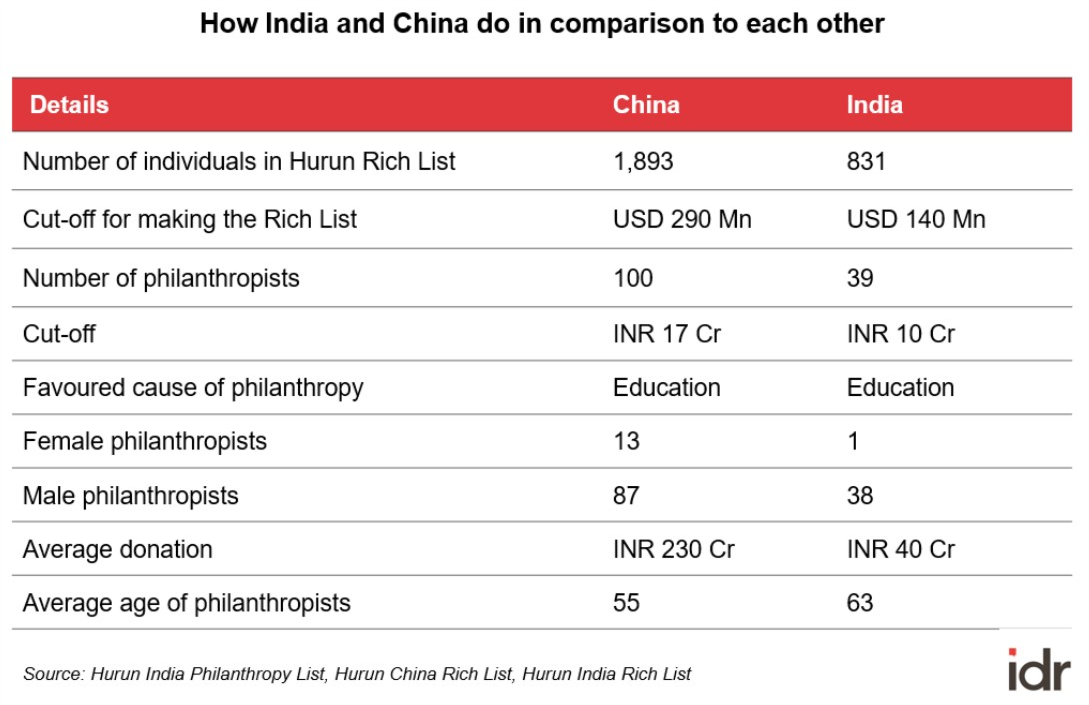

Of course, the pieces I link to speak mainly of western donors. Little or no data means it is nearly impossible to make any sense of Indian philanthropy—much of it is money given out of personal bank accounts of individuals, not structured trusts. But what we do know is that Indian billionaires are far less generous than Chinese billionaires when it comes to parting with their money for charitable causes.

They couldn’t care less

If you were struck by the sheer political apathy to the migrant exodus that took place during the lockdown, this new research will not come as a surprise. Yale University’s Nikhar Gaikwad and Gareth Nellis have found that politicians do in fact discriminate against internal migrants.

Their experiments revealed that fictitious migrants are 23% less likely to receive a call-back from a councillor in response to a letter requesting assistance, compared to an otherwise similar ‘native’. Those migrants who can signal that they are registered to vote in municipal ward elections are more likely to get a response than those who don’t.

Because politicians believe that migrants are unlikely to participate in their re-election, they ignore their needs and requests for help.

Well, as long as there’s a good reason then.

It's a rap!

Finally, here’s a Bhojpuri rap song that captures all the emotions, angst and complexities of the migrant crisis. Performed by Bollywood star Manoj Bajpayee—himself Bihar's export to Mumbai—the song is titled “Mumbai Main Ka Ba” or What's in Mumbai? I understand a little bit of the language and the song moved me to tears. There are English subtitles too—watch for the sass, the heartbreak and the goosebumps!

Sincerely,

Amee Misra

Contributing Editor, IndiaSpend

Twitter LinkedIn

You are receiving this email as you are subscribed to the IndiaSpend mailing list. Any views or opinions are the author's own.

So very interesting and informative. I am sure the menu will keep growing - in and from your hands!

This is a great initiative. I love ths potpourri of economic, social, political & popular culture articles. Keep it going!