Hello

IndiaSpend is happy to launch ResearchWire, our first curated newsletter. This fortnightly email is a compilation of the latest research and thinking on India’s health, education, gender, environment, and the economy.

ResearchWire is curated by Amee Misra, a development economist who has worked in varying capacities with DFID, UNWomen, UNICEF, UNDP, Centre for Policy Research, and the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. She has worked on a range of development issues including public financial management, health, education, international trade, and gender. Amee also sits on the board of India Development Review.

In the first edition today, we discuss falling fertility rates, COVID's impact on violence against women, India's complex food value systems and school education.

Be careful what you wish for

We’ll soon have to think of a new fall guy, as ‘population’ may no longer be the reason why everything in the world is upside down. See this BBC piece summarising a recent Lancet study, on how fertility rates and population growth are declining across the world. World population is set to substantially decline by 2100. This is mainly because women are having fewer children. Fertility rates (the average number of children a woman has) are falling globally mainly due to improvements in women’s education, their increasing participation in the workforce, and increased access to contraceptives.

India’s SRS (Sample Registration System) Survey for 2018 (most recent data) reflects the trend. See this on how barring eight states, all Indian states have achieved “Replacement Fertility” i.e. an average of 2.1 children over a woman’s lifetime, which means that the population will stop growing, and only replace itself over time.

Bihar is now the only Indian state where a woman in 2018 was likely to have over three children in her lifetime.

Also, more old people: Many southern Indian states have had replacement fertility rates for some time now and are now facing a different issue—a higher share of senior citizens in their populations. The Lancet study finds that this may be the way other countries are going globally too.

Now why is that a problem?

Simply (perhaps even a little simplistically) put, fewer people in the working-age group will mean smaller economies and lower growth—but not necessarily smaller needs. There will be more dependent adults for every working-age person who needs work, pays taxes and funds an increasing need for pensions. If this issue interests you, I recommend you read the original Lancet study—or at least the discussion at its end.

There isn't enough food. But it’s not that simple

Sudha Narayanan outlines the many complexities of India's food value chains in a blog based on her new study.

There is no one way in which India's lockdown impacted its food markets.

For instance, even as prices faced by the producers (farmers, wholesalers) declined during the lockdown (closure of restaurants, catering businesses, and the migrant exodus), thanks to increased frictions in the supply chain (limited labour availability, higher transport costs and uncertain logistics), consumer food prices in most urban areas increased.

Different products were also impacted differently. If you were a farmer growing wheat, you received a higher price as the government stepped up procurement for the PDS, but if you grew perishables such as fruits and vegetables, you faced widely fluctuating prices and greater logistical challenges. At the retail end, the neighbourhood kirana shops (mom and pop stores) navigated challenges most successfully, embracing technology and tying up with private aggregators.

All in all, the study concludes that India's food supply chains have proven themselves to be resilient. But also that food insecurity remains a problem. If you're a non-economist, the linked piece may be a bit of a heavy read but the logic is spelled out clearly and is easy to follow.

Our men continue to shine

New NBER working paper here by Saravana Ravindran and Manisha Shah on the impact of India’s lockdown on violence against women. The numbers are there for you to see—our men have not disappointed.

Domestic violence and cybercrime increased during the lockdown, most where the lockdowns were the strictest (red vs green zones). At the same time, rape and sexual assault complaints decreased as there were fewer women in public places/ transport/ workplaces. This doesn't take into account marital rape because (1) no data and (2) not a crime in India, so obviously no data.

Also, where more husbands viewed domestic violence as “justified”, there were larger increases in domestic violence complaints.

An important takeaway from this research is that not all violence against women is the same. The paper also shows that attitudes towards domestic violence are important because they have real implications for the actual incidence and reporting of this violence.

Women face a “portfolio of dangers” and there is no one policy that will address them all.

The paper also led me to the most recent NFHS (National Family Health Survey) report (2015-16) that found that wife-beating isn't quite as unacceptable as we'd like it to be.

52% of women and 42% of men in India believe that a husband is justified in beating his wife.

If you’d like to read something more positive, see this for results from a survey carried out earlier this year that points to signs of young, educated women challenging the status quo around marriage, parenting, work, friendship, and politics.

What about the kids?

An excellent blog here by the folks at the Centre for Global Development on ways in which COVID-19 will shape the future of education. They find that in the long term, there will be a lot less money available for education—both under domestic budgets and via aid. When budgets contract, trade-offs are inevitable, and it is unlikely that education will beat other choices. Millions of children will not return to school and learning losses will worsen inequalities. Not all countries have effectively transferred learning programmes to online channels or others such as TV and radio. EdTech will not be the equaliser many imagine it to be. In fact, investments in edtech are likely to increase learning inequalities and further disadvantage the poorest children. Finally, high-stake exams remain unfair, and disruptions in private sector education markets will lead to greater strain on government funded schools.

If you’re interested in or work in education policy, this is a very good piece to read. Lots to chew on and all the evidence you’ll need.

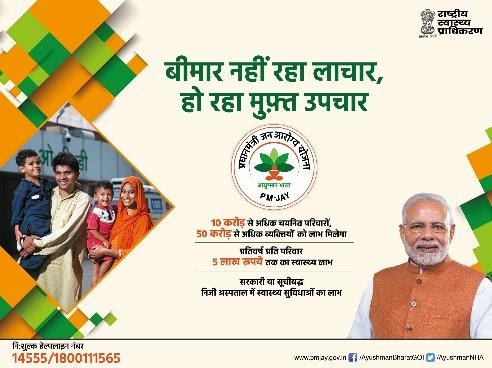

The many woes of PMJAY

Those enrolled under the Government of India’s PMJAY scheme—that offers free health coverage for the poor—are a disgruntled lot. There is a difference between people’s expectation (cashless) and the reality (less cash). Like most insurance policies, PMJAY covers different treatments only up to a certain limit so when hospital bills exceed that, customers are asked to cough up the difference. This is to be expected, of course, but the real issue here is one of messaging. Since the key message around PMJAY is “muft upchar” or free treatment, people who’d like to get that are understandably very unhappy. Given how widespread and aggressive the advertising around the scheme has been, it is hard to blame this on people missing the fine print.

Also in the context of the PMJAY, I found this very good piece on the importance of knowing the costs of providing healthcare. If you don’t know what it costs to provide treatment, how will you deliver PMJAY in a cost-effective way? Heck, how will you deliver it at all?

The short answer is, you can’t. Because the government does not know the costs of different treatments, it is unable to negotiate prices at which private providers are able and willing to offer them. You have unhappy (and non-participating) private hospitals, and an ineffective government programme. Here’s a long read by HBR on how to solve the cost crisis. Read also this on the political economy of the PMJAY, arguing that without adequate regulations and investments in public healthcare, the scheme is likely to divert public funds to private institutions.

If you’d like to read still more on healthcare, here is a whole book (downloadable) by Amanda Glassman and others on principles that countries with limited resources can apply to design their healthcare packages. (Spoiler: They will need to know their healthcare costs.)

Finally, if you enjoy numbers and geometry, here is a great nerdy piece on how a question that has occupied history’s greatest mathematicians is now central to how we can safely open schools, offices and public spaces. What is the most efficient way to arrange circles in a plane?

Sincerely,

Amee Misra

Contributing Editor, IndiaSpend

Twitter LinkedIn

You are receiving this email as you are subscribed to the IndiaSpend mailing list. Any views or opinions are the author's own.

Thank you Amee and Samar for this very thoughtfully written newsletter. Especially happy to see education as a focus area. Anustup

Best wishes in all your journalistic work. Please consider: why are we not thinking of using prophylaxis against covid 19 which is being used in many countries including Germany, Bangla desh, Nigeria, part of US and Austraila? It is simple, safe and only needs a prescription from a doctor. It is a short-term loading dose of Hydroxycholroquine *800 mg first day, 400 mg for six more days, 400 mg on day 8 and 10 and then 400 mg once a week.. Many of us, doctors, have been taking it for several months. It is best used with caution in cardiac patients and epileptics.