IndiaSpend ResearchWire - August 14

Hello,

In the second edition of ResearchWire by IndiaSpend, we discuss air pollution, declining corporate social responsibility funds to development organisations, the disproportionate impact of the pandemic on the vulnerable (lower-ranked castes), and a survey on willingness to take a vaccine if it becomes available.

If you’ve missed the first edition, you can read it here.

Get to that bucket list, fast

Folks at the Energy Policy Institute of The University of Chicago (EPIC) have a new report out on the Air Quality Life Index (AQLI), and it isn’t looking good.

The average resident of Delhi-NCR loses over 9 years of life, thanks to air pollution. The average Indian resident loses more than 5 years.

You can access the India Fact Sheet here. You can also go here for an interactive tool that allows you to play with the data—see the numbers for other parts of the world and travel back in time to see how these have evolved. A summary news report, if you’d like to read more, is here.

Note that Government of India had declared a “war on pollution” in 2019 with the launch of the National Clean Air Programme (NCAP) to reduce particulate pollution by 20-30% by 2024. While I couldn’t find an official update, a civil society tracker has found slow progress in disbursement of funds.

When politicians give economists ulcers

Read an excellent two-part series here on how the smog towers proposed for Delhi have no scientific basis. They are attractive for governments because they are visible, don’t require handling opposing interest groups (the polluters can go on with business as usual), and use everyone’s favourite solution to all problems—technology. But there is no evidence that they work. And since there is only so much public money—money spent on them is money taken away from everything else.

Delhi’s upcoming smog towers are a textbook example of governance that makes economists miserable, and politicians delirious with joy.

PM may Care but others do too

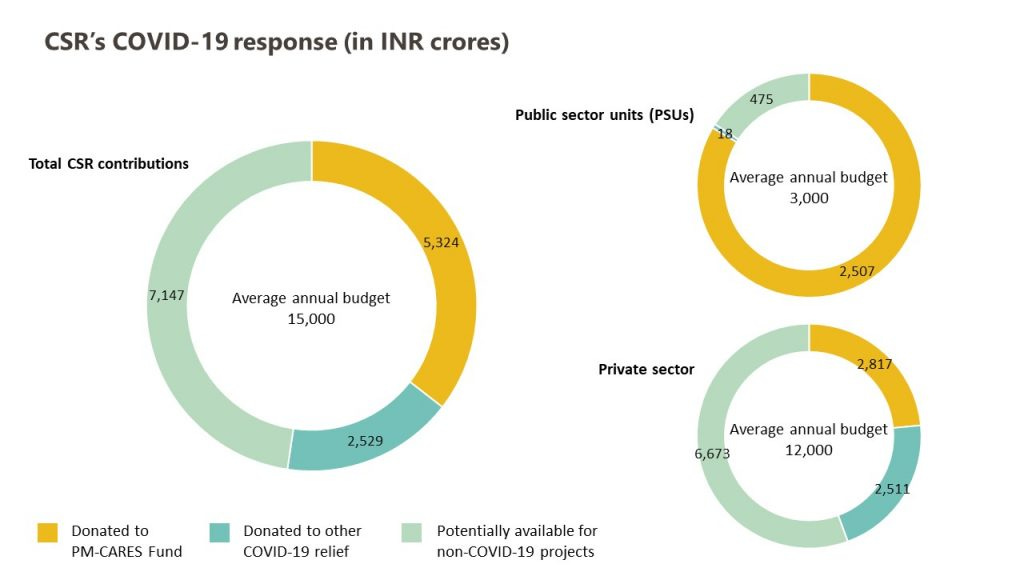

Read this great piece on CSR (corporate social responsibility) funding during the pandemic—where it’s going, who it’s from, and who gets it. While historically the PM National Relief Fund receives about Rs 200 crore annually though CSR, PM-CARES managed to garner more than 25 times this amount in a much shorter time frame. And at least enough to fund over 21.5 million COVID tests.

This is not new money, but money diverted from many other development organisations. Key CSR contributors of some of the most underfunded regions have already committed funds elsewhere.

Source: India Development Review’s graphic, based on data compiled by Sattva

PM-CARES appears to have funnelled a large amount of capital away from the non-profits.

This should concern you because it weakens the ability of civil society to provide nimble, decentralised support on ground. Note also that PM-CARES continues to face questions around its transparency and accountability—none of which anyone has deigned to address.

Stop calling it The Great Leveller

Evidence continues to come in about how the pandemic and the lockdown have disproportionately impacted those who were vulnerable to begin with. Ashwini Deshpande and Rajesh Ramachandran find that while all caste groups lost jobs in the first month of the lockdown, job losses for lowest-ranked castes are 3 times greater.

They also find that caste did not matter when people were educated: For those who had more than 12 years of education, there were no caste-based differences in job losses.

Their results don’t point to any new discriminatory behaviour per se, but they do reflect the underlying inequalities in the structure of India’s job market. Lower-ranked caste groups are overrepresented in vulnerable jobs.

See also this on how workers in India are willing to forego as much as 10 times their daily wages to avoid work that conflicts with their caste identity. I won't pretend I know or understand the many complexities that underpin these choices but if you believe there is no caste in India, there’s a bridge I’d like to sell you.

You can’t make me take the vaccine

A vaccine for COVID-19 is turning into an excellent Public Policy 101 case study. You already know that there are many challenges to the development, manufacturing and distribution of a vaccine, but that's not all.

It turns out that once you have a vaccine ready and waiting, not everyone will queue up for it.

A new study based on a survey of 4,000 slum dwellers in Lucknow and Kanpur found that if a COVID-19 vaccine is introduced, 36% of those surveyed will only get vaccinated if they did not have to pay for it. 5% of the population will not get vaccinated at all.

Now, 95% are willing to take the vaccine and that’s not terrible. The authors note that this is higher than such willingness in at least 7 European countries (Denmark, France, Germany, Italy, Portugal, the Netherlands, and the UK).

So what's the policy implication?

We will need to subsidise the COVID-19 vaccine—even provide it for free. This should be a no-brainer for most vaccines any way, especially for diseases that have such high rates of infection. The social benefits of getting vaccinated are far larger than an individual’s, and the state must step in.

We need a celebrity. When people know and understand the disease, they are more likely to take the vaccine (though information that leads to panic reduces compliance). India's experience with polio seems to agree with wider findings that celebrity endorsements impact people’s healthcare decisions.

Actor Amitabh Bachchan has been the face of India’s polio eradication campaign.

India was declared polio-free in 2014.

This world is designed (literally) for men

Finally, did you know that even though the majority of the global healthcare workforce are women (70%), masks and other protective equipment (PPEs) are designed for men’s bodies? Expectedly, this leaves the women at very high risks. The larger issue of women working in a world designed for men is so pervasive that we don’t see it. It defines the ‘normal’.

If this interests you, do read Caroline Criado Perez’s outstanding book, ‘Invisible Women: Exposing Data Bias in a World Designed for Men’. It tells you why women’s loos have longer queues, or why cars are more dangerous for women. If you won’t read the book, read this piece that shares some of Perez’s findings. I promise you, you won’t look at the world the same way again.

Sincerely,

Amee Misra

Contributing Editor, IndiaSpend

Twitter LinkedIn

You are receiving this email as you are subscribed to the IndiaSpend mailing list. Any views or opinions are the author's own.